I was recently in Silverton and revisited a paper I wrote in college for a class called “The Contested American Countryside.” The writing is fine, but I found it to be a nice refresher on the history of the area for my passing through with Almila.

In a high alpine valley encircled by the San Juan Mountains, sits the town of Silverton, Colorado. Stepping into Silverton is like walking onto the set of an old Western film. One can imagine outlaws such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid walking down the dirt roads amongst the town’s Victorian style architecture and steam locomotives. This, along with the abundant abandoned mines and mills which dot the surrounding peaks, the old aerial trams and discarded rail lines, represent the town’s traditional mining heritage. Today, the town supports a year-round population of 638 that proudly resists town sprawl, outside control, and any sort of chain business. According to the town’s Chamber of Commerce, Silverton “is a simple town, based on a simple quality of life, simple ways, simple needs of the people.”

The old mining town’s official beginning came in 1860 with the discovery of gold and silver. After the expulsion of the Ute Indians, the area was open for settlement. The town of Silverton was platted in 1874, and by 1875 the town’s population had doubled. Much like other mining towns, Silverton’s mining history has seen many boom and bust cycles, dictated by the variable national market, periodic recessions and wars, and the fluctuating prices of metals. Silverton’s last major operating mine, Sunnyside Gold, closed in 1991.

While there are still treasure hunters and small-scale mines about, Silverton’s economy is defined by tourism. Silverton is the destination of travelers from Durango on the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad and a desirable stop for those traveling along Colorado state highway 550. The train has been operating since 1882 and over the past half century has allowed mass tourism into the world of Silverton. For better or worse, this fact has inexorably changed the town of Silverton. While tourism has apparent benefits, the associated psychological, cultural, political, and economical costs can be high. I will explore some aspects of this while critically looking at film-induced representations of the town and its history.

The town has avoided the fate of many other Western towns with mining heritage with its respectable attempts to diversify its economy. I will consider some of the possible directions that the town of Silverton can take while exploring many of the dominating themes in Silverton’s narrative.

A Historical Background of Silverton

The expulsion of the Ute Indians in Colorado began with the discovery of gold near Denver in 1958. For generations before the Euro-American settlers ventured west into the Rockies, the Utes roamed the entirety of Colorado, northern New Mexico and much of Utah. Gold drew miners West into the mountains, encroaching onto Ute territory. A succession of treaties followed, all of which reduced the extent and reach of Ute land. The first treaty in 1868 forced the Ute Indians out of central Colorado, the second treaty in 1872 forced them out of the San Juan Mountains, and the third treaty in 1873, the Brunot Treaty, forced the Utes out of Colorado completely. To see a map of Ute Indian Territory based on these three treaties, see addendum I.

In 1960, a group of prospectors made their way up the Animas River Valley into what is now modern day Silverton. While the discovery of gold and silver here promised an incredibly lucrative future, conflicts with Ute Indians and the Civil War led many of the settlers to temporarily withdraw from the area. With the conclusion of the Civil War in 1965, prospectors returned in even greater numbers despite the existing treaties and trespassed onto Ute land. With the Brunot Treaty in place, the land where present day Silverton and San Juan County is was opened to white settlement.

From the early 1880’s up until the early twentieth century, Silverton was the nexus for the surrounding mining camps at Rico, Ophir, Ouray, and Telluride. Silverton also supported many other small towns that sprang up around the areas largest mines. These included Gladstone, Eureka, Animas Forks, Howardsville, Red Mountain, and Chattanooga. A seemingly endless supply of silver allowed Silverton to establish its foundation. To export precious metals out of the town, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad (D. &R.G.R.R.) established a line from Durango to Silverton. Today, this line is more commonly known as the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad (D. &S.N.G.R.R.). Because of the rail system, Silverton was truly able to prosper. An individual by the name of Otto Mears planned out three other lines, the Rio Grande Southern (R.G.S.), the Silverton Railroad (S.R.), and the Silverton Northern (S.N.), that would extend from Silverton to nearby satellite towns as minerals continued to flow from the mines. The 1880’s were the best times for Silverton. At this time, the town itself supported a population of around 5000 people, almost ten times the current population. To round out the town, a post office, town hall, courthouse, and library were built during this time.

The Silver Panic of 1893 left the town of Silverton and surrounding mining settlements in San Juan County in economic squalor and resulted in the mass flight of miners to nearby gold camps, a new hope for economic prosperity. This event left the remainder of Silverton and San Juan County “eerily quiet” and a climate of “self-deceiving hope” kept the residents’ spirits warm in spite of their reality. The following century in Silverton was quite typical of mining towns. The town’s economy was characterized by several boom and bust cycles guided by undulating market trends and prices of metals. During World War I and World War II, precious metals lost a great deal of their value as more useful metals such as zinc and copper, were used to build military infrastructure. This impeded many gold and silver mining endeavors and resulted in the closure of numerous mines.

In 1929, the Shenandoah-Dives Mining Company established the Mayflower Mill to recover gold, silver, lead, zinc, and copper from ore mined at the Mayflower mine. The mill and associated mines remained Silverton’s largest employer for nearly 25 years. The mine endured market and metal price fluctuations while others struggled and closed. Therefore, it is not hard to imagine just how detrimental its closure was to the town of Silverton. At the conclusion of the Korean War in 1953, competition from foreign mines and falling metal prices were too much for the once resilient Shenandoah-Dives. While other mines would remain active, such as Sunnyside Gold, its closure marked the point in time when mining would no longer dominate Silverton’s economy. Tourism had begun to supplement Silverton’s economy in the early twentieth century. The industry grew to such significant proportions during the 1950’s that it assumed a larger share of the economy than it had previously.

A Brief History of Tourism in Southwestern Colorado

The ruggedly beautiful scenery of Southwestern Colorado represented something much more than its physical and visual reality. Like the Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, and Yosemite Valley, Southwestern Colorado served as an embodiment of Western nationalism. It’s grandeur, dramatic topography, and empirical beauty gave the early expansionists of the West satisfaction and a sense of assurance and power as Americans. The Rockies were no longer an obstacle, but rather a valued destination for reasons other than its minerals. Travel via railroads in the West by those who could afford the opportunity to do so, resulted in the socially constructed narratives of the American West. In his book Devil’s Bargains, Hal Rothman states, “Railroad travel in the West manifested the power of American wealth, creating a pattern in which the act of tourism affirmed American society.” Furthermore, railroads enabled travel to rural places by a predominately-urbanized population, which resulted in the construction of the commodified landscape.

The inception of tourism in Southwestern Colorado came when early American explorers of the mid-1860’s realized both the economic potential and the rugged beauty of the region’s natural resources. In 1867, a journalist from Springfield, Massachusetts, Ovando Hollister concluded that the connection of Rocky Mountain region to the rest of the United States by railways would open a “new world to science, a new field of adventure to money and muscle, and new and pleasant places of summer resort to people of leisure”. And that is just what had happened.

In the 1890’s, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad used the scenery of the Rockies to their advantage and began advertising and looking for the support of middle-class tourists who could afford a trip throughout the Rockies. With a budget of $60,000 per year, the Denver and Rio Grande marketed the Rockies of Southwestern Colorado resulting in the rise in tourism to the region. While many of the rail lines are no longer in operation, the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railway serves “hundreds of thousands of sightseers and railroad enthusiasts.” Traveling via refurbished narrow gauge steam locomotives, visitors are provided with a means of observing the scenery of Silverton and the rugged topography of the San Juans from a unique perspective, away from the confines of state highways into the ‘wilderness’.

The Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad

The Durango and Silverton narrow gauge railroad was established and began its operation in 1882. From the railroad’s inception, people were encouraged to come along for the spectacular scenery between Durango and Silverton. By the 1940’s, visitors came from all over to experience the scenery up the Animas Canyon from Durango to Silverton, the decaying buildings and mining apparatus, the crisp blue Animas River, the pine and spruce lining the rail corridor, and the snow-capped peaks towering to heights of 14,000 feet.

The narrow gauge rail that makes up the present day Durango and Silverton Railway was once part of an elaborate system of rail lines that made up the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad system. Today, the line is preserved in its original fashion along with its steam engines, engine facilities at Durango, water service centers along the route, and the northern terminus at Silverton. At one point, the branch line was connected to the three aforementioned short lines, the Rio Grande Southern, the Silverton Railroad, and the Silverton Northern. These lines were abandoned around the conclusion of World War II, a reflection of the decline of mining in Silverton and much of the Coloradan southwest. Beginning in 1950, the Denver and Rio Grande began running summer tourist trains before the closure of Silverton’s most lucrative mine in 1953. The closure of Shenandoah-Dives signified an end to mining in the district, as well as the end of the line’s year round operation. Fortunately, the Rio Grande’s Silverton line would go on to make a successful transition from a working line in relation to mining to a scenic line for tourists in the 1950’s. With a bit of help from its appearances in 1950’s Western film, the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad became a desired tourist destination.

The Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad stimulates Silverton’s economy more so than any other operation. As railroad owner Al Harper has said, “The railroad is the economic engine that drives Silverton’s summer tourism-based economy.” Many business owners within Silverton have expressed concern about railroad operations though. Grand Imperial Hotel owner George Foster expresses concern for the amount of time tourists get to explore Silverton once they arrive into town from the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad. Foster states that tourists “get about an hour and a half” which amounts to “time to eat and pee.” Unfortunately, this is the result of federal regulations regarding railroad operations. Any more time spent in Silverton would mean that train crews would exceed the maximum allowable workday. Al Harper, owner of the railroad is willing to work with Silverton residents in trying to come up with a mutually beneficial solution in order to procure business for Silvertonians.

Silverton and its Hollywood Glory Days

In the 1950’s, after the decline of the mining industry, the town of Silverton and the San Juans were exploited for another valuable resource- its scenery. Silverton and its remarkable scenery has long been the background for many 20th and 21stcentury films, particularly westerns such as Ticket to Tomahawk (1950), Around the World in 80 Days (1956), Night Passage (1957), How the West was Won (1962), and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). According to the Silverton Standard’s primary contributor Mark Esper, “the arrival of the old Western movies in Silverton meant a fistful of dollars for the local economy and, as locals recalled recently, plenty of fun and excitement along for the ride.” Silverton resident Bill Swanson recollected, “The locals didn’t mind, people in town were excited; it was a big deal. The movie people hired just about every local in town (referring to Run for Cover 1955).” Silverton’s big Hollywood heyday concluded in the late 1960’s and only a handful of films have been filmed there since including City Slickers (1991), Over the Top (1987), and The Prestige (2006). Regardless of Hollywood activity in Silverton today, the presence of its streets, mountains, buildings, and mines in Western films has left a lasting impact on the town and the way it is marketed and represented today. Its image makes it powerfully attractive to its visitors. However, this representation isn’t entirely accurate.

Cowboys and Indians: The Historical, Social, and Cultural Ramifications of Western Film

After viewing several Western’s that were filmed in Silverton such as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), Run for Cover (1955), and Denver and Rio Grande (1952), this conclusion can be made: Indians often play a supporting role in Western film and were almost always portrayed as racially inferior. While this was more pronounced in Run for Cover and Denver and Rio Grande, all at least have subtle nuances alluding to this. According to Will Wright in the book The Wild West: The Mythical Cowboy and Social Theory, the “Indians symbolize racial savagery whenever they appear in the cowboy myth, but they do not always appear.” Wright goes on to discuss that the dominating conflicts that arise in Westerns are typically between whites and whites, not whites and Indians. In her book West of Everything, Jane Tompkins discusses the reason why she chose to omit a lengthy discussion on Indians in Western film and literature:

“After the Indians had been decimated by disease, removal, and conquest, and after they had been caricatured and degraded and Western movies, I had ignored them too. The human beings who populated this continent before the Europeans came and who still live here, whose image the Western traded on— where are they? Not in Western films. And not in this book either”.

Perhaps all that is left to remember the Utes who inhabited the San Juan Mountains surrounding Silverton, is the wilderness area named after a band of them, the Weminuche. The wilderness area is part of the greater San Juan National Forest, part of an even larger federal entity that has systemically forced Indians off of their home territory and onto small reservations. The tradeoff here has been the myth of pristine wilderness. In addition, an array of cheap appropriated Indian novelties can be bought at the local Silverton trading posts and gift shops.

Other films that portray Indians as “bestial savages” and “noble savages,” both represented as impediments to progress, are Red River (1960), The Unforgiven (1960), Apache (1955), and Dances with Wolves (1990). While these films were not filmed in Silverton, they contribute to the grand narratives of Western film that draw visitors to towns that exude the “Wild West” image and the frontier myth such as Silverton. The essence of the frontier myth is best described by Richard Slotkin, as quoted in The Wild West:

“At the core of the Myth is the belief that economic, moral, and spiritual progress are achieved by the heroic foray of civilized society into the virgin wilderness, and by the conquest and subjugation of wild nature and savage mankind. According to this Myth, the meaning and direction of American history— perhaps of Western history as a whole— is found in the metaphoric representation of history as an extended Indian war.”

This presents a large void in the history of the Silverton area. Even though Ute Indians have inhabited the San Juan Mountains of Southwestern Colorado for many generations longer than white European-Americans, they are hardly given acknowledgment in the history of Silverton and when they are, they are often grossly misrepresented and portrayed as they are in Western film.

The popular history of the United States is built on the aforementioned mythic lore. Cowboys, conductors, miners, and frontier settlers are glorified and have seemed to prove to an “adorning public that once life had held no tedium, no sense of entrapment.” This along with other socio-culturally directed expectations dictate the community and their respective landscape. In the words of Michael Woods, “as tourists expect to see the landscapes exactly as seen on screen, cinematic tourism can demand the blurring of fictional and ‘real’ landscapes”.

A Modern Portrait of Silverton

Today, the town of Silverton is almost entirely dependent on tourism. During the summer months, Silverton caters to thousands of tourists. Many come from the all over the world and most arrive to the town via the Durango and Silverton Narrow Gauge Railway. The railroad alone brings 170,000 into the town. The train runs from May to the end of October. When the train reaches town, visitors are allotted a couple short hours to shop at the Western motif shops and numerous trading posts, dine at a local eatery, and wander the old Western streets lined with Victorian style buildings. Thousands of others make their way through Silverton via Highway 550 and the Million Dollar Highway between Silverton and Ouray. The entire town of Silverton is currently included in a federally designated National Historic Landmark District, the Silverton Historic District. There are many authentic experiences to be had: witness a mock gunfight, travel via horseback in the San Juans, pan for gold, explore old mines such as the Mayflower Mill and Old Hundred, traipse around the abandoned mining settlements of Animas Forks, Eureka, and Howardsville, take a guided stagecoach tour, etc. But behind all of its prototypical Western allure, it is still just a typical rural American town. Nothing explains the convergence of the actual and imagined realities of modern Silverton than the following quote by Will Wright from his book Rocky Mountain Divide: Selling and Saving the West:

“Visitors crane their cameras at odd angles to avoid including the many trailer houses, propane tanks, satellite dishes, snowmobiles, and scrap heaps in there carefully framed images.”

The surrounding Weminuche Wilderness and the San Juan Mountains provide recreationalists with an abundance of opportunities to backpack, fish, hunt, and climb. Bike trails, hiking trails, all-terrain vehicle (ATV) and off-highway vehicle (OHV) trails transect and crisscross the landscape.

Aside from tourism, a great deal of Silverton’s residents are employed in amenity and tourism-based jobs. Because of this, winter months have typically been economically challenging for Silverton. With the majority of the town’s revenue entering the community in the summer, winter is characterized by unemployment and isolation. However, several factors are making the winter months much more manageable including a diversifying economy, winter-based tourism, and the addition of educational institutions.

Because of Silverton’s high elevation and location within the mountains, the community is subjected to its locations variable weather conditions. On average, Silverton receives upwards of 200 inches of snow a year making for long, harsh, and unforgiving winters. If you need to leave town, it is mandatory to have a four-wheel drive or an all-wheel drive vehicle. Sometimes, even this isn’t enough- the town is situated between two mountain passes in the direction of Durango to the South and Ouray to the North. Since there are no foothills between the high peaks surrounding Silverton and the town itself, avalanches have the ability to make their way into town and cause serious damage. In an interview with Silverton resident, Cheryl Lubin, she stated, “The people that live here year-round WANT to be here. They say if you’re still here after one of the San Juan winters, than there’s a good chance you’ll stay.”

After the closure of Sunnyside Gold in 1991, 800 individuals were left unemployed. While tourism made up a significant portion of the economy then, there were certainly not enough jobs to employ the population that was left unemployed. Consequently, many people either left town and found jobs elsewhere or wrestled with unemployment. In a 2000 report issued by the town of Silverton, mayor Ernest Kuhlmen illuminated the economic plight that characterized Silverton in the 1990’s and early 2000’s:

“The winter population is less than 15% of the summer population, the winter economy is less than 10% of the summer economy and the community has experienced the highest rate of winter unemployment in the entire state of Colorado since 1992.”

Silverton’s economic development corporation, San Juan Development Association, has played an integral part in the recent course of business development. Formed in 1991 following the closure of the Sunnyside Gold mine, the corporation’s primary goal has been to “encourage new economies that could replace mining,” while boasting “a mission of increasing employment, income and self-sufficiency in San Juan County.” One of Silverton’s prime objectives in recent years has been to diversify its economy. The town of Silverton is located within one of Colorado’s “Enterprise Zones.” Colorado defines an “Enterprise Zone” as “an economically distressed area.” Consequently, tax incentives are offered to businesses and organizations to stimulate the local economy by creating new jobs and investment. The result of this has given hope to the small post-boom town for future economic prosperity and security.

According to an article in the Gunnison Country Times entitled Mountain Towns Mine Next Boom, “the entrepreneurial spirit that has long defined the West is alive and well.” In the past five years, Silverton has experienced a surge of small business activity that consists of seven start-up and seven relocating businesses including Venture Snowboards, Montanya Distillers, and Scotty Bob’s Skis Custom Shop, all of which have provided opportunity for local employment. Many of the young entrepreneurs that make Silverton their home are not after limitless growth; instead they are “set on preserving Silverton’s ‘rough-around-the-edges character’” and seem to be more interested in creating a higher quality of life for the community. These businesses have other reasons for choosing Silverton. According to the local chamber of commerce, these reasons include,

“An incredible mountain setting, a down-to-earth community, a skilled and well educated workforce, available commercial real estate, affordable rents, attainable housing, exceptional schools, innovative childcare, phenomenal air quality, internet and supply line infrastructure, minimal commuting, and freedom from the crime, gang, and drug problems that plague other communities.”

While Silverton has seen a recent surge in business activity, concurrently, the town has acquired the Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies, the Mountain Studies Institute and other non-profit organizations as a result of recruitment efforts. In addition, two new ski areas, Silverton Mountain and Kendall Mountain, have contributed to local job creation and growth.

The Mountain Studies Institute is an exciting and important addition to the town of Silverton. The independent non-profit organization’s mission is to “enhance understanding and sustainable use of the San Juan Mountains through research and education” which is also applicable to mountain systems and communities around the world. The Mountain Studies Institute engages the local community and school system, as well as creating partnerships with several institutions like Durango’s Fort Lewis College, the University of Colorado at Boulder, and United States Forest Service. In doing so, the Mountain Studies Institute provides educational opportunities for the local community and for students, including internships, grants, and educational programs geared towards Silverton’s school.

Kendall Mountain Recreation area and Silverton Mountain provide Silvertonians with winter fun and several employment opportunities. Unlike Aspen, Vail, Telluride, Crested Butte and other mountain ski towns that see thousands of tourists daily, Silverton’s Kendall Mountain caters to the locals and Silverton Mountain draws in expert backcountry skiers. Each year, fewer and fewer seasonal summer businesses close because of the growing interest in skiing. Canyon View Motel owner Cheryl Lubin affirms that with the opening of the two ski resorts, “winters in Silverton have gotten much, much better”. In addition to these ski mountains, there are also a few local businesses that do most of their business in the winter. Mountain Boy Sledworks and Venture Snowboards’ most busy months are in the winter. Mountain Boy Sledworks owner Karen Hoskin states that one of the best things about her business seeing its busiest months in December is that “it’s the opposite season from what drives Silverton’s economy, so it is employing people” when many would usually be dealing with economic distress and unemployment. Venture has created several year round jobs for Silverton locals. In an area of the country commonly referred to as “ski-country,” these businesses are sure to continue their success.

Additionally, there is tubing, sledding, ice-skating, skijoring, dog sledding, snowmobiling and incredible winter hiking and camping opportunities.

The businesses of Silverton are almost all locally owned by folks who call Silverton home. Unlike many towns throughout rural America, Silverton provides many amenities to locals that are found in more urban and suburban neighborhoods such as Pilates, Indoor Cycling, Yoga and Dance. Many restaurants stay open year round and are owned and operated by culinary graduates. While the town doesn’t have a Wal-Mart super store, it has a small grocery store, liquor store, hardware shop, and many other essential stores that adequately serve the needs of its residents.

As of 2002, Silverton’s public school has adopted the nationally recognized Expeditionary Learning Outward Bound Curriculum. On average, the Silverton School maintains an enrollment of around 70 children from kindergarten to twelfth grade in a historic three-story brick building that recently underwent an 11 million dollar renovation. Many students are involved in travel teams for soccer, rock climbing and ski racing. Most students graduate high school here and become successful local business owners, Peace Corps Volunteers, or pursue higher education. Many Silverton children get an early start to education through the Silverton Family Learning Center, which uses a pre-primary program inspired by Silverton’s Reggio Emilia. The program is geared towards children from birth to age five that gives children a strong start towards a lifetime of curiosity and responsibility. According to Silverton’s Chamber of Commerce, the Silverton School’s students score higher than the national average across the board.

Like other mountain towns such as Crested Butte, Telluride, and Durango, housing costs have tripled since the late 1990’s. For Silverton, housing costs are still significantly lower than the other towns, which have become highly gentrified and the object of many vacationers. Silverton’s rising housing costs are a reflection of the high vacation home demand and expectations of the growing market generated by interest in Silverton Mountain, the incredible San Juans, and all of the other draws that bring people to the town. To provide the community with attainable and affordable housing, the town of Silverton has taken a proactive approach in planning new housing development that consists of 53 new units of single family, multi-family and duplex housing which has already begun development. In addition, this development will likely expand local business.

The Future of Silverton

The community of Silverton has vehemently opposed much of the change that has plagued many other Colorado mountain towns— gentrification, loss of local power, rampant and unplanned development, and homogenization. Although many feel that the town has a long way towards economic stability, Silverton’s recent surge in business activity, establishment of mountain research institutions and educational programs has certainly put the town on the right course. According to Silverton resident Scott Fetchenhier, Silverton and the San Juans are once again “experiencing a resurgence of the mining industry now that the price of base metals is climbing”. This has provided an added optimism to the residents of San Juan. While it may not be entirely ecologically sustainable, it will temporarily diversify Silverton’s economy.

With the growing interest in the town of Silverton, many outsiders will continue to buy up real estate. Currently 54.5 percent of Silverton’s houses are vacant, the majority of which are for seasonal, recreational or occasional use. Many big blocks of mining claims are being bought up and sold for cabin sites. Some residents claim that the town’s last big boom will be real estate.

Perhaps there will be resurgence in Western film that will put Silverton back into the spotlight. For now, the town will most likely remain dependent on tourist dollars, but not just summer ones now. Because of the two specialized educational institutions that have been added to Silverton’s portfolio, the town has a stronger likelihood to flourish. One thing is certain: The town of Silverton is resilient, resourceful, and likely to endure the challenges of the future with pride.

Addendum I

Works Cited

“About MSI | Www.mountainstudies.org.” About MSI | Www.mountainstudies.org. Web. 13 Nov. 2012.

Bold, Christine. Selling the Wild West: Popular Western Fiction, 1860 to 1960. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1987. Print.

Brown, David L., Louis E. Swanson, and Alan W. Barton. “Tourism and the Natural Amenity Development.” Challenges for Rural America in the Twenty-first Century. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2003. Print.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Dir. George R. Hill. Perf. Robert Redford, Paul Newman, Katharine Ross. Ken Films, 1969. DVD.

Crum, Josie Moore. Three Little Lines; Silverton Railroad, Silverton, Gladstone & Northerly, Silverton Northern. Durango, CO: Durango Herald News, 1960. Print.

Dahl, Jordyn. “Tourism Chugs Right along.” The Durango Herald [Durango] 22 June 2012: Print.

Dahl, Jordyn. “Tourists Flock to Colorado amid Worries about the State of Summer Blazes.” The Durango

Denver & Rio Grande. Dir. Byron Haskin. Prod. Nat Holt. By Frank Gruber. Perf. Edmond O’Brien, Sterling Hayden, and Dean Jagger. Paramount Pictures, 1952.

Dewitz, Kathi. “Stepping Back in Time.” Silverton Standard & the Miner [Silverton] 7 June 2012: Print.

Esper, Mark. “‘a Colorado Treasure'” Silverton Standard & the Miner [Silverton] 8 Oct. 2009: Print.

Esper, Mark. “Planning Begins for Downtown Improvements.” Silverton Standard & the Miner [Silverton] 18 Oct. 2012: Print.

Esper, Mark. “The Silver (ton) Screen.” The Durango Herald [Durango] 25 May 2012: Print.

Esper, Mark. “Silvertonians Want Train Passengers to Stick around.” Silverton Standard & the Miner [Silverton] 15 Oct. 2009: . Print.

Esper, Mark. “A ‘sweeter’ Downtown?” Silverton Standard & the Miner [Silverton] 19 Nov. 2009: Print.

Esper, Mark. “‘train Keeps Rolling'” Silverton Standard & the Miner [Silverton] 4 Oct. 2012: Print.

Fetchenhier, Scott. “New Boom on the Horizon?” Silverton Magazine. San Juan Publishing Group, Inc, 29 May 2012. Web. 1 Dec. 2012. <http://www.silvertonmagazine.com>.

Holladay, Matthias. “Thoughts on Silverton, CO.” Telephone interview. 3 Dec. 2012.

Hollister, Ovando James. The Mines of Colorado. Springfield, MA: S. Bowles, 1867. Online.

Lubin, Cheryl. “Some Questions about Silverton and Tourism.” Message to the author. 6 Dec. 2012. E-mail.

Milner, Clyde A. “Cowboys, Outlaws, and Violence.” Major Problems in the History of the American West: Documents and Essays. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1989. Print.

Milner, Clyde A. “Imagining the West.” Major Problems in the History of the American West: Documents and Essays. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath, 1989. Print.

Opportunity. Proposal. San Juan 2000 Development Association, 4 Dec. 2008. Web. 3 Nov. 2012.

O’Rourke, Paul M. Frontier in Transition: A History of Southwestern Colorado. Denver, Colo. (Rm. 700, Colorado State Bank Bldg., 1600 Broadway, Denver 80202): Colorado State Office, Bureau of Land Management, 1980. Online.

Rothman, Hal. Devil’s Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth-century American West. Lawrence, Kan.: University of Kansas, 1998. Print.

Run for Cover. Dir. Nicholas Ray. Perf. James Cagney, John Derek, and Vivica Lindsfor. A Paramount Picture, 1955. DVD.

Shoemaker, Will. “Mtn. Towns Mine next Boom.” Gunnison Country Times [Gunnison] 30 Oct. 2008: A12-13. Print.

Silverton Chamber of Commerce. Silverton, CO. Silverton: Silverton Chamber of Commerce, 2012. Print.

Silverton, CO. Silverton: Silverton Chamber of Commerce, 2012. Print.

Silverton, Colorado Saves Its Newspaper. Perf. Mark Esper., 10 Sept. 2009. Web. 20 Nov. 2012. <http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=silverton+colorado+news paper&oq=silverton+colorado+newspaper&gs_l=youtube.3…8384.10507.0.1 0621.10.10.0.0.0.0.192.799.8j2.10.0…0.0…1ac.1.EZKoex5fBVw>.

“Silverton, CO.” San Juan County Historical Society. Web. 21 Oct. 2012. <http://www.silvertonhistoricsociety.org/>.

Smith, Duane A. Colorado Mining: A Photographic History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, 1977. Print.

Tompkins, Jane P. West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns. New York: Oxford UP, 1992. Print.

“Welcome to Silverton Colorado’s Welcome Site.” Silverton Colorado Tourism Site, Web. 10 Nov. 2012.

Woods, Michael. Rural. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Wright, John B. Rocky Mountain Divide: Selling and Saving the West. Austin: University of Texas, 1993. Print.

Wright, Will. The Wild West: The Mythical Cowboy and Social Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2001. Print.

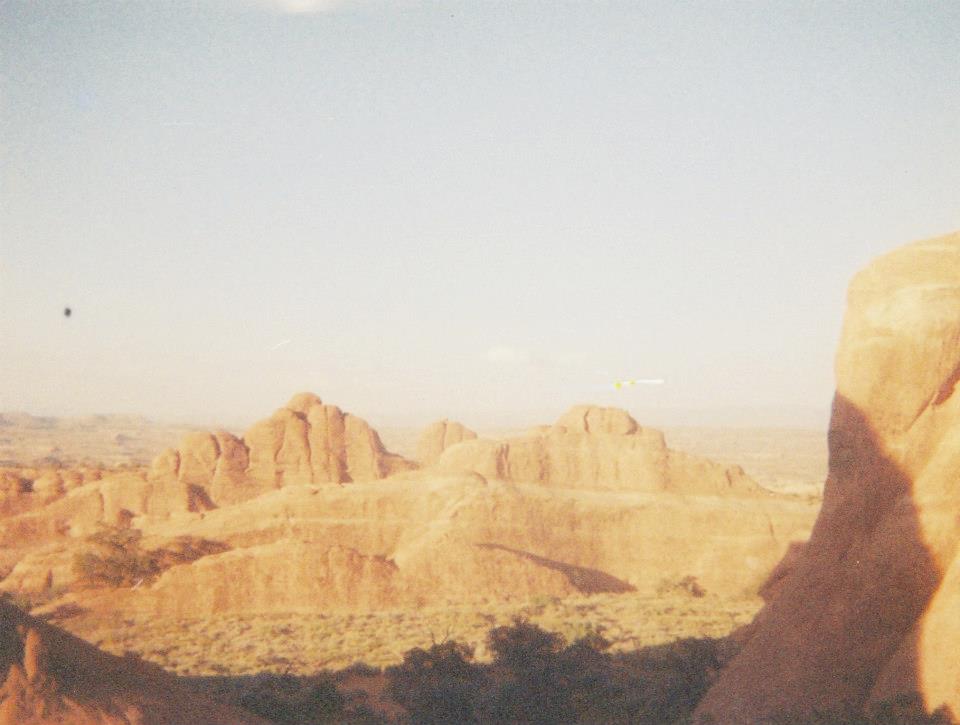

Like a handful of times before, my car pointed towards the Four Corners. I can’t explain how the place makes me feel and I won’t try–anyone who has been there understands.

Like a handful of times before, my car pointed towards the Four Corners. I can’t explain how the place makes me feel and I won’t try–anyone who has been there understands.